This is Ignaz Semmelweis. He was a brilliant man who failed.

Now this is a little bit of a long story, but bear with me I think it’s realy interesting.

In 1846, the young Hungarian obstetrician began a position on the obstetrics ward at Vienna General Hospital. His ward had a problem: women who came to his hospital were much more likely to die if a doctor delivered their baby than if a midwife did.

The discrepancy in maternal death rates was so pronounced the ward had become notorious: in 1846 when Semmelweis began at the hospital, the maternal mortality rate on the doctor’s ward was 11.4%, compared to 2.8% on the ward run by midwives. Women in labour begged Semmelweis not to send them to the doctor’s ward, and some even started ‘accidentally’ giving birth on their way to the hospital to avoid running the risk.

This was apparently a prudent decision: Semmelweis’ notes remarked that even giving birth on the street had better outcomes than at the hands of the doctors.

The cause of these excess deaths was almost exclusively down to much higher rates of a sickness nicknamed ‘childbed fever’.

But why remained a mystery, which Semmelweis was determined to solve.

He set about identifying the different variables that could be behind this and began to test them:

Was it overcrowding? No – the midwife ward was always more crowded.

Was it the ward location? No – the two were in very close proximity.

Was it the birthing technique? No – while there were small differences in approach, it didn’t explain the difference.

Was it a snowball effect, where women were being scared sick by priests on their way to deliver last rites to others in the grip of the fever? Nope.

Semmelweis was stumped, and it haunted him.

In March 1847, his close friend and colleague Jakob Kolletschka was accidentally cut by one of his students while conducting an autopsy.

Within two weeks, Jakob was dead. As Semmeweis read his friend’s post mortem, the morbid procession of pathology he had seen time and time and time again stared back at him.

And finally the pieces fell into place.

What were the doctors doing that the midwives weren’t? Autopsies.

I’m sorry… what?

So it turns out, at the teaching hospital where Semmelweis worked, it was fairly standard for the doctors to go straight from chopping up cadavers to delivering babies without washing their hands. As is perhaps a bit more obvious to our modern sensibilities, this was a bit of an infection risk.

Semmelweis had a new hypothesis to test.

His working theory was that ‘corpse particles’ had some role in instigating the disease, and did so when ‘absorbed’ by open wounds. In this way, childbed fever was not a unique phenomenon, contamination of wounds with dead or decaying matter – generally- caused disease.

In the 1820s, autopsies had become an increasingly common feature of medical education and practice. Therefore by the 1840s, it was not uncommon in teaching hospitals like the Vienna General Hospital for doctors hands to carry the ‘good old hospital stink’ as they strolled into the delivery ward (😖). This was what he decided to target.

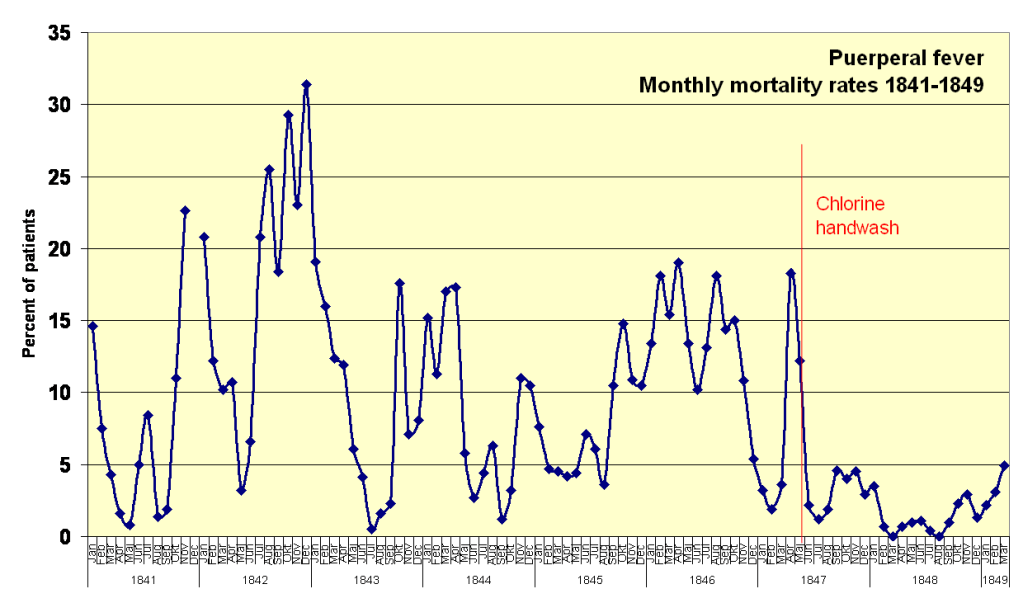

The experiment involved asking doctors to rinse their hands with chlorine wash before conducting examinations or deliveries. The wash was selected as it proved the best method of getting rid of the smell – with bad air still a leading theory of disease spread at the time. As luck would have it, it was also a powerful disinfectant.

The experiment was an emphatic success.

Image: Power.corrupts – Own work, Public Domain

Almost instantaneously, the death rates on the doctor’s ward dropped dramatically, and the discrepancy between the two wards disappeared. The next March would be the first month on record where not a single patient died from childbed fever at the hospital, the second would follow in August.

This was in 1847.

Upon his discovery Semmelweis eagerly wrote of his findings to the Austrian medical establishment and other leading obstetricians. His students presented lectures and submitted papers to scholarly societies and journals across the continent, from Austria to France the UK.

Semmelweis’ died almost 20 years later on 13 August 1865.

At the time of his death, childbed fever still ran rampant across Europe’s maternity wards.

His work had been met, for the most part, with either indifference or active hostility. He died of sepsis in an insane asylum, driven mad by the weight of all the death and suffering he felt powerless to stop.

As Semmelweis spiralled, on the other side of the continent, Joseph Lister was independently reaching very similar conclusions inspired by the work of Louis Pasteur. The day before Semmelweis’ death, Lister would conduct the first successful test of his antiseptic technique in surgery.

An obstetrics textbook published by the Austrian medical establishment in 1870 lauded the importance of aseptic technique, but it was Lister’s carbolic acid, not Semmelweis’ calcium hypochlorite that they promoted, even though calcium hypochlorite is the one that is still widely used in medicine today.

If the authors were aware of the similar discoveries made closer to home on a maternity ward in Vienna decades earlier, they didn’t mention them.

The story of Semmelweis today is well known, often told in terms of a personal tragedy. This is undeniably true, not just because of his own sad fate but also the countless lives that could have been saved if his findings had been awarded the same attention that Listers would be twenty years later.

The story that is told often focuses on how ingenuity and passion was ignored and extinguished by a callous and self interested medical establishment. How the pure pearls of science were cast before an ignorant society of self interested swine.

But if this is all we take away from the story of Ignaz Semmelweis, we badly miss the point.

Semmelweis was without question a dedicated, intelligent and compassionate doctor and his discovery was genuinely groundbreaking. But brilliance alone was not enough. He failed because he could not convey the significance of his findings to his colleagues, nor generate the momentum to effect widespread change.

Now to be fair some of this was beyond his control. The fact his discovery was immediately followed by one of the most politically unstable years in European history can’t have helped.

But he also didn’t help himself. To some extent the common explanation that the medical establishment was offended at the idea they were causing so many deaths because of bad hygiene was indeed true, but that was also true for Lister and he managed.

It’s worth bearing in mind that germ theory was not yet by any means scientific consensus at this point, meaning that there wasn’t an obvious mechanism by which the new method would work. To be fair to the medical establishment, most times a random junior scientist comes up with a radical and inexplicable theory and calls for widespread change in medical practice to follow it, skepticism is pretty reasonable.

What is more, Semmelweis himself wouldn’t actually formally write up his findings until much much later, and most of the initial communication of his work was done by his students – many of whom didn’t grasp the scope of his theory.

The idea that childbed fever could spread between people, and that doctors could be vectors for spreading it, had been presented in 1843 in an essay in the New England Journal of Medicine by US physician Oliver Wendell Holmes. This idea had been received with interest, although it was limited to this specific disease, and handwashing was presented as one of several possible methods by which doctors could try to reduce spread.

Because of the misunderstandings by Semmelweis’ students, many – particularly those in the UK – considered Semmelweis’ work to be broadly a confirmation of those of Wendell Holmes, when in fact it was far more profound.

Even in his 1847 notes Semmelweis seems to have appreciated that ‘any old dead matter’ could cause childbed fever, and indeed could cause infections – in general – like that which had killed his friend. He also identified this as the sole cause, going against the prevailing theory at the time that the disease was caused by multiple factors at once. Consequently, by removing the ‘corpse particles’ with disinfectant those infections could be almost completely prevented.

Reticence to explain his work himself wasn’t Semmelweis’ only problem though. His main challenge seemed to be his knack for rubbing people up the wrong way.

In the two years he spent in Vienna hospital as first assistant on the obstetrics ward, Semmelweis had successfully slashed the mortality rates that had made the hospital infamous. But when he applied for an extension of his post he was snubbed by his boss in favour of Carl Braun, another obstetrician with whom Semmelweis frequently argued and who was vocally critical of the ‘corpse particles’ theory.

He then applied for a more junior position where he could at least lecture and teach, but again his application was rejected. The final straw came in 1850 when, after a full 18 months, he was finally allowed to teach but only ‘theoretical’ obstetrics, where he could only use mannequins rather than cadavers for his teaching.

He then went back to Hungary, where again he transformed the survival rates in his local hospital, but again nobody would listen to him or take up his methods.

Semmelweis did not hide his frustrations which – understandably – mounted as his findings were systematically either ignored or actively attacked by the leading scientists of the day. His letters addressed to eminent medical researchers and indeed at some points ‘all obstetricians’ were described as ‘highly polemical and superlatively offensive’, laden with insults and accusations of murder and butchery.

It was these increasingly hysterical letters that led to his wife and colleagues admitting him to the asylum.

Lister took a different approach.

He fastidiously wrote up his findings and conducted experiments, delivered lectures and built relationships within the scientific community. He responded politely and objectively to criticisms of his work in letters published in academic journals – remaining courteous even when his critics did not offer him the same grace.

By doing this, Lister changed people’s minds.

Lister was still a passionate and emotional man – but the way he presented his work was not.

Good science communication is hard, but it is also incredibly important.

It’s all too easy to view the story of Ignaz Semmelweis individual tragedy, of a brilliant, compassionate man, and forget that ultimately that wasn’t enough.

But the tragedy is far larger in scope: countless deaths could have been avoided if the findings had been recognised.

It doesn’t matter how right we think we are, how stupid or lazy or evil we think those who disagree with us or slow us down might be, or how much all of that eats us up inside. What matters is what happens.

It is telling that Semmelweis’ nemesis Carl Braun – despite aggressively disagreeing in public with the corpse particle theory – nevertheless maintained the handwashing regime introduced by Semmelweis when he took over the ward in Vienna General Hospital.

Even as he lectured against the corpse particles theory, he didn’t deny that something about handwashing seemed to be helping.

There was common ground to work with.

It’s hard not to get angry when we see important things misrepresented or ignored, and when incorrect claims get perpetuated while misinformation invariably takes the limelight

There are many times when I see things being spread and believed that I worry will have unintended consequences, or are straight up wrong, where I feel just like Semmelweis in his letters. It’s hard to take things in good faith when they piss you off.

But we must always remember that we will not convince people by shouting out them (just as we will not be convinced by being shouted at).

We will convince and be convinced if we can do the legwork to know our stuff inside out, build trust by listening, bring down the temperature by avoiding personal attacks, be measured in what we say and honest about what we don’t know, and be open to being wrong ourselves.

If we feel what we are saying is not landing, we need to think about why that might be, and build the necessary bridges to start fixing it.

It doesn’t always work, but a lot of the time it really does, and we have to try.